Comentarios sobre el arte de Elías Henoc Permut y el contexto cubano

Traducción: Herbert Toranzo (poeta y narrador).

Podemos abandonar un lugar, pero no el pasado; el pasado es testarudo… y para estar en el presente, a menudo lidiamos con un pasado y le damos un nuevo sentido; un pasado que no pocas veces empleamos para, de una forma u otra, localizar y mantener definida nuestra identidad.

La identidad personal en la cultura occidental es compleja, sea uno quien sea, y viva donde viva. Con toda certeza ha sido esta una cuestión manifiesta en la obra de muchos artistas contemporáneos. Las tradiciones étnicas y religiosas heredadas juegan con nuestra psiquis, como también las tradiciones relacionadas con la tutela paternal, los prejuicios y las jerarquías sociales, entre otras, y todas abren un camino o erigen un obstáculo… muy pocas veces son neutrales.

En el arte cubano reciente se han tratado las tradiciones y símbolos de la Santería, el Palo Monte y otros cultos de distintas maneras, principalmente por figuras como Manuel Mendive, José Bedia, Marta María Pérez Bravo, Belkis Ayón, por nombrar sólo a algunos, y estos marcadores y signos de las tradiciones religiosas tributan, por medio de sus obras, a todo un abanico de aspectos sociales y culturales. En cada uno también se tributa a un pasado que sigue estando muy presente.

No ha de ser difícil entonces, en ese contexto, abordar la obra de Elías Henoc Permut con igual sensibilidad y reconocimiento de la presencia de otra tradición religiosa, aun cuando esta no sea tan generalizada en Cuba como la Santería o el Palo Monte en tanto ejemplos. Lo que se puede observar es una respuesta compartida a la energía y la potencia del simbolismo en cada una, a medida que hace resonancia con la ‘identidad’ y la expresión artística.

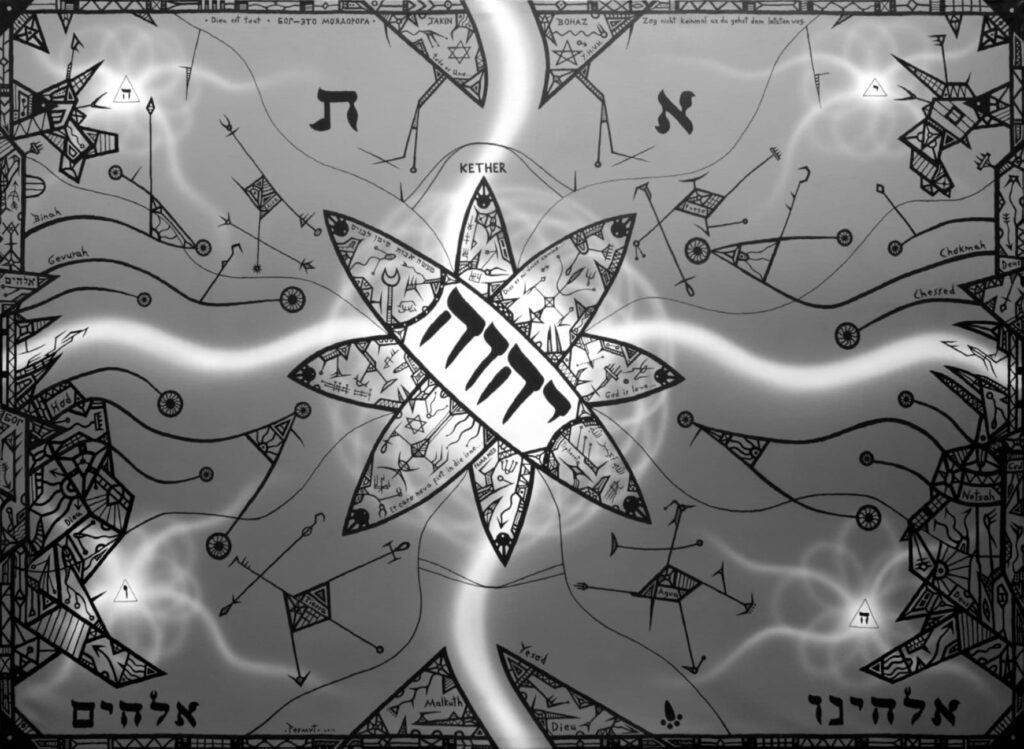

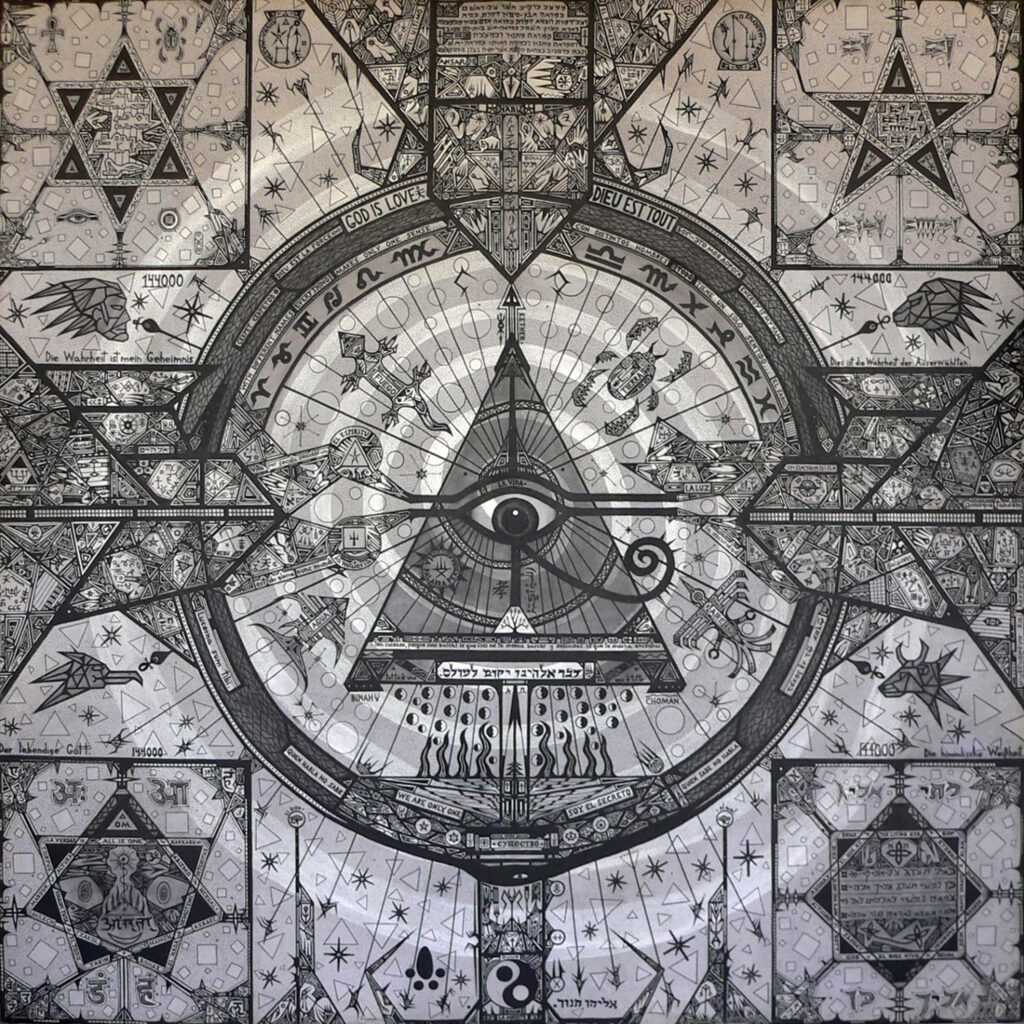

La cábala, el judaísmo esotérico o místico, tiene mucho que ver con el poder del simbolismo, y lo que yo veo en la obra de Permut es, a veces, una descripción altamente tradicional de las jerarquías y el significado de los diversos pictogramas, y en otras ocasiones una exploración más personal de las interacciones potenciales de estos elementos individuales, que confieren una apariencia fresca e invitan a una nueva relación. El hecho de nombrar a Dios, hasta el punto que ese hecho mismo pueda existir o permitirse en este mundo, en el ámbito del texto y la fe judía, es también fundamental para la obra de Permut; aunque, al igual que sucede con la cábala, su presencia pudiera no ser reconocida por la mayoría de los que la miren. Pero, sin ella, para el artista su trabajo perdería todo significado y coherencia; carecería de lógica y estaría incompleta.

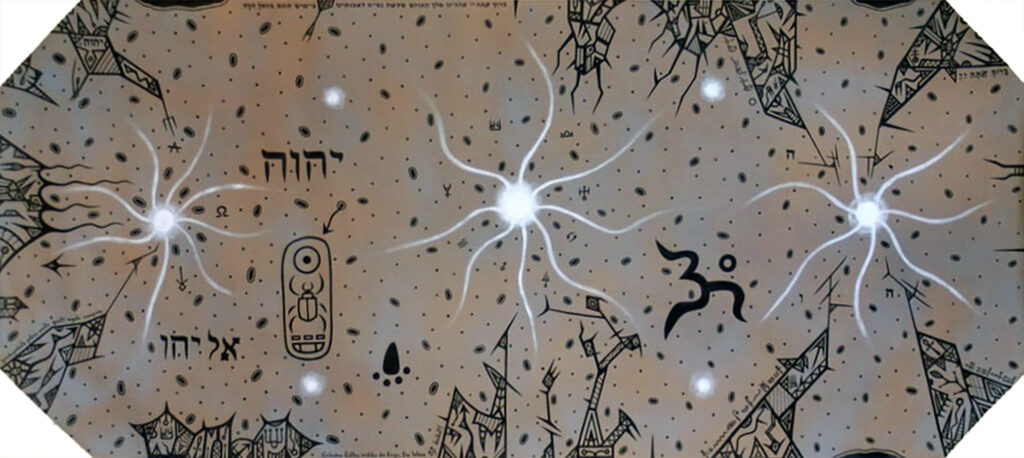

Se debe entender que la simbología egipcia en la cábala no sólo es evidente sino fundamental. Este conocimiento nos permite admitir la larga historia de tan mística tradición en el judaísmo. Moisés guió a los judíos para salir de Egipto, pero Egipto, en esta presencia mística y simbólica, permanece con los judíos en la simbología de la cábala.

Incluso sin ninguna comprensión de la cábala, estos cuadros pueden —y yo creo que deben— prender una chispa en la imaginación del espectador. Nuestro ‘vocabulario’ para describir nuestra realidad es, muchas veces, limitado. ¿Qué es el mapa cósmico que llena el cielo nocturno? ¿Es tan sólo el que se basa en la ‘visión’ grecorromana? Por supuesto que no. Los nativos americanos perciben por completo las relaciones entre las estrellas, y tienen sus propios nombres para cada constelación que sean capaces de ver. Nuestra capacidad de ver más allá de nuestras angostas definiciones de tiempo y espacio, por medio de la realidad de otras personas, amplía nuestra comprensión y discernimiento. Tiene el potencial de suscitar nuevas y cardinales preguntas.

En algunas piezas, Permut se identifica y establece un vínculo más personal con el cielo nocturno. Orión es sin dudas una de las constelaciones que le interesan, aunque para él no manifiesta la tradicional proyección del cazador, sino que en sus lienzos activa un sendero de vida eterna. Esta visión, con una mirada nueva o diferente, es transformadora y contemporánea, puesto que nos pide que no aceptemos la tradicional lectura de los astros, sino que hallemos algo más personal, relevante y de mayor sentido en nuestras propias vidas. Este es un enfoque vitalmente necesario y crítico que, en manos de un artista, puede llevar al público a percibir el mundo de manera diferente, con una actitud más abierta y mayor sentido de participación individual en la creación de nuestra realidad.

No podemos dejar la obra de Permut sin hacer referencia, además, a la habilidad que despliega en el arte pictórico. Sus cuadros son luminosos y precisos en el detalle y la composición. Son cautivantes y magnéticos. Poseen una luz interior que se percibe en lo profundo, y una energía vibrante. Se remontan al misterio de la fe, y evocan el alma del artista.

Robert Schweitzer ha sido curador, educador y profesor adjunto de Arte Contemporáneo. Durante los años 80 realizó curadurías para muestras en museos, entre las que se incluyen importantes obras de Hans Haacke, Jenny Holzer, Alfredo Jaar, Joseph Beuys, Betsy Damon, Robert Smithson y Louise Lawler, entre otros. También fue curador y redactó el catálogo para la primera exposición de fotografías de Margaret Randall en los Estados Unidos, en 1988. Además, fue curador en el Museo Everhart en 1985, tiempo durante el cual instaló la muestra itinerante “De la colección de Sol LeWitt” y fue organizador y moderador del simposio que incluyó a Lawrence Weiner, Louise Lawler, Andrea Miller-Keller y John Paoletti. Desde mediados de los años 90 hasta su retiro en 2017 fue curador de la Colección Maslow, la cual se trasladó en 2007 a la Universidad de Marywood, donde Schweitzer desarrolló un programa de estudios curatoriales para emplear dicha colección como medio de enseñanza. En 2002 organizó y estuvo a cargo de la curaduría de una muestra a gran escala de artistas latinoamericanos, además de redactar su catálogo y moderar varios simposios vinculados a ella. Esta exposición incluyó a artistas como Nadín Ospina, Eugenio Dittborn, Cecilia Vicuña, Lilianna Porter, Leandro Katz, Alfredo Jaar, Luis Camnitzer, Carlos Garaicoa, entre muchos otros. También, durante los últimos años 80 y a lo largo de los 90, Schweitzer fue uno de los pocos curadores de los Estados Unidos que asistieron a cinco Bienales de La Habana consecutivas (desde la tercera hasta la séptima). Los archivos personales de Schweitzer han estado disponibles y muchos estudiantes e investigadores del mundo los han utilizado.

Comments on the art of Elías Henoc Permut and the Cuban context

One can leave a place but not the past, the past is stubborn… and to be in the present, we often struggle with a past and make new meaning from it, a past that we often use in one form or another to locate and held define our identity.

Personal identity in Western culture is complex no matter who you are and where you live. This has certainly been an issue manifested in the works of many contemporary artists. Inherited ethnic and religious traditions play on our psyche, as do traditions of paternalism, prejudices and social hierarchies, among others, and they either provide a path or a barrier… they are hardly ever neutral.

Within recent Cuban art the traditions and symbolism of Santería, Palo Monte and other cults are treated in varying ways, mainly by artists such as Manuel Mendive, José Bedia, Marta María Pérez Bravo, Belkis Ayón, to name only a few, and these markers and signs of religious traditions speak through their work to a range of contemporary social and cultural issues. And in each they also speak to a past that remains very present.

It should not be difficult therefore, within this context, to approach the work of Elías Henoc Permut with a similar sensitivity and recognition of the presence of another religious tradition, though clearly one not shared as widely within Cuba as Santería and Palo Monte as examples. What can be observed is a shared response to the power and potency of symbolism in each as it resonates with ‘identity’ and artistic expression.

The Kabballah, esoteric or mystic Judaism, is very much about the power of symbolism, and what I see in Permut’s work is at times a highly traditional depiction of the hierarchies and meaning of the various pictograms, and at other times a more personal exploration of the potential interactions of these individual elements, giving a fresh look and inviting a new relationship. The very naming of God, to the extent that this naming can even exist or be permitted in this world within the Jewish text and belief, is equally central to Permut’s work, though as with the Kabballah, its presence may not be recognized by most viewers, but without it for the artist, his work would lose all meaning and coherence, it would lack logic and would not be whole.

To understand that Egyptian symbolism in the Kabballah is not only evident but central, and this knowledge enables you to recognize the long history of this more mystical tradition within Judaism. Moses led the Jews out of Egypt but Egypt, in this mystical symbolic presence, stays with the Jews within the symbolism of the Kabballah.

Even without any understanding of the Kabballah these paintings can —and I believe should— spark the imagination of the viewer. Our ‘vocabulary’ to describe our reality is often a limited one. What is the cosmic map that fills the night sky? Is it just the one based on the Greco-Roman ‘view’? Of course not. Native Americans see entirely relationships among the stars and have their own name for each constellation that they readily see. Our ability to see beyond our narrow definitions of time and space through the reality of others expands our comprehension and insight, and has the potential to raise new and meaningful questions.

In certain works, Permut identifies and undertakes a more personal with the night sky. Orion is clearly one of those constellations that interests Permut, though for him it does not manifest the traditional projection of the hunter but on his canvases it activates a path to eternal life. This seeing with new or different eyes is transformative and contemporary as it asks us not to accept the traditional reading of the stars but find something more personal, relevant, and meaningful in our own lives. This is a vitally necessary and critical approach that in the hands of an artist can move the viewer to see the world differently, with a more open attitude and sense of personal participation in the creation of our reality.

We cannot leave Permut’s work without also commenting on the skill he exhibits in his craft of painting, they are luminous and precise in detail and composition. They are captivating and compelling, they have an internal light that is deeply felt, and an energy that vibrates. They evoke the mystery of the faith, and the soul of the artist.

Robert Schweitzer is a former curator, educator, and adjunct professor of contemporary art. During the 1980s he curated museum exhibitions that included major works by Hans Haacke, Jenny Holzer, Alfredo Jaar, Joseph Beuys, Betsy Damon, Robert Smithson, and Louise Lawler, among others. He also curated and wrote the catalogue for the first exhibition of Margaret Randall’s photographs in the U.S. in 1988. Additionally, he was the curator at the Everhart Museum in 1985. During which time he installed the traveling exhibition “From the Collection of Sol LeWitt” and organized and moderated a symposium that included Lawrence Weiner, Louise Lawler, Andrea Miller-Keller, and John Paoletti. From the mid 1990s until his retirement in 2017 he was the curator of The Maslow Collection which in 2007 moved to Marywood University, where he developed a program in curatorial studies using the Collection as a hands-on resource. In 2002 Schweitzer curated a large-scale exhibition of Latin American artists for which he also organized and wrote the catalogue and moderated a series of symposia; this exhibition included such artists at Nadín Ospina, Eugenio Dittborn, Cecilia Vicuña, Lilianna Porter, Leandro Katz, Alfredo Jaar, Luis Camnitzer, Carlos Garaicoa, among numerous others. Also, during the late 1980s and through the 1990s Schweitzer was one of the few curators from the U.S. who attended five consecutive Havana Biennials (from the third to the seventh editions). Schweitzer’s former personal archives have been used by many students and researchers throughout the world.